THE GLORY OF CARECA AT NAPOLI

15/11/2017

by GARY THACKER

Antônio De Oliveira Filho was born in the city of Araquara in the Brazilian state of São Paulo on 5 October 1960. His nickname, Careca – which roughly translates as ‘bald’ – came to him during his childhood due to his likeness of the famous Brazilian clown

Carequinha who, very much like the young boy, had a fulsome mop of black hair.

His early career was spent with local club Guarani, whom he joined in 1978. The young striker’s pace, natural ability to score goals and uncanny knack of knowing how to be in the right place at the right time to finish off attacks quickly blossomed, and his first season brought him 13 goals in just 28 games. For a newcomer to the league, it was an impressive opening statement, but there was more to come. In his five years with the club he scored more than a century of goals, and his continuing development brought him to the attention of São Paulo FC. In 1983 he moved to the state capital and joined the

Tricolor.

By now he had already broken into Brazil’s national team and was earmarked to make the trip to Spain for the 1982 World Cup finals, but injury thwarted those ambitions. He was, however, a part of the squad that finished as runners-up in the 1983 Copa América. The 1986 World Cup would be his big international coming out party, and his performances in that Mexican summer were to provide the last piece in the jigsaw that saw him recognised as a world-class striker. They would earn him a move to Serie A and the

Partenopei.

Before that, though, he would enjoy a hugely successful three-year period with São Paulo. Again, he demonstrated his ability to be successful without any need for a settling-in period. His first season brought him 17 goals, tying the total of the renowned

Zico and finishing as joint-second top scorer. The total made the transfer look a shrewd investment by the

Tricolor and he would go on to underscore that assessment, despite a second season in which he failed to appear in a single game in Série A.

It was back to the old routine the following season, as Careca plundered a dozen goals in just 17 games. In the 1986 season, his goals would guide São Paulo to the championship and Copa de Brasil double. He was top scorer in both competitions and was awarded the Bola de Ouro, unsurprisingly recognising him as the season’s outstanding player.

By now he was also the focal point of the

Seleção’s attack, and after the disappointment of 1982, when Brazil lost out to Italy in the second group round thanks to a Paolo Rossi hat-trick and a 3-2 defeat in a pulsating game, the 1986 tournament offered a chance of redemption for one of the perennial tournament favourites. They had been unable to include Careca in 1982, but he would play a full part in the tournament in Mexico.

Brazil skated through the initial group stage, winning all three games. Careca scored three times, netting the winner against Algeria and a brace in the 3-0 victory over Northern Ireland. In the round of 16, he again scored in the 4-0 rout of Poland. In the quarter-final against France, a 1-1 draw took the game to penalties, and despite having converted from 12 yards against the Poles, Careca was surprisingly not chosen to take one of the five spot-kicks. At the end, a miss by Júlio César saw the

Seleção eliminated again.

Careca at Guarani

If the tournament was ultimately a disappointment for the national team, it was a huge success for Careca and confirmed his ranking on the international stage as one of the top strikers on the planet. He finished as second-top goalscorer, trailing

Gary Lineker by a single strike. With the summer over, the

Tricolor succumbed to the lure of the lira, and Careca decamped from Brazil to join Napoli for a reported 4 million lira fee. It turned out to be a bargain buy for the newly-crowned Serie A champions as Careca swapped São Paulo for the San Paolo.

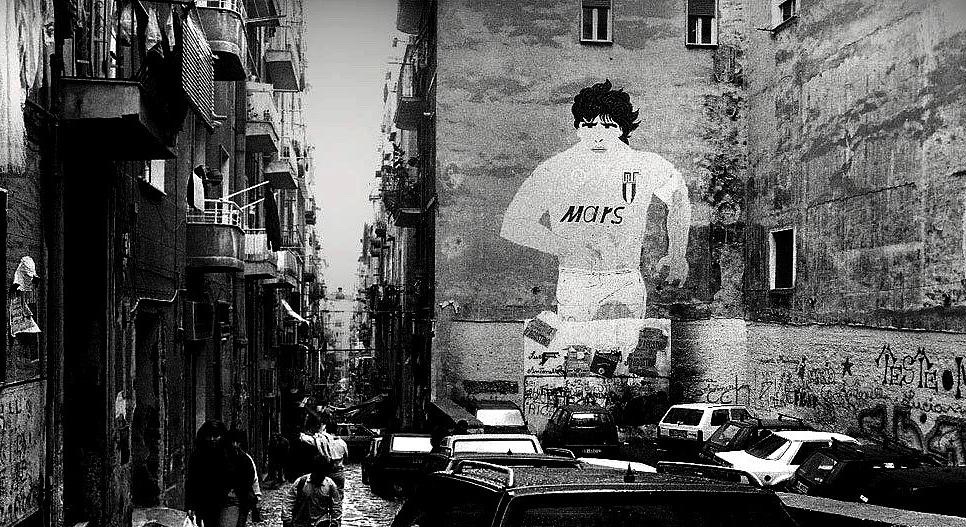

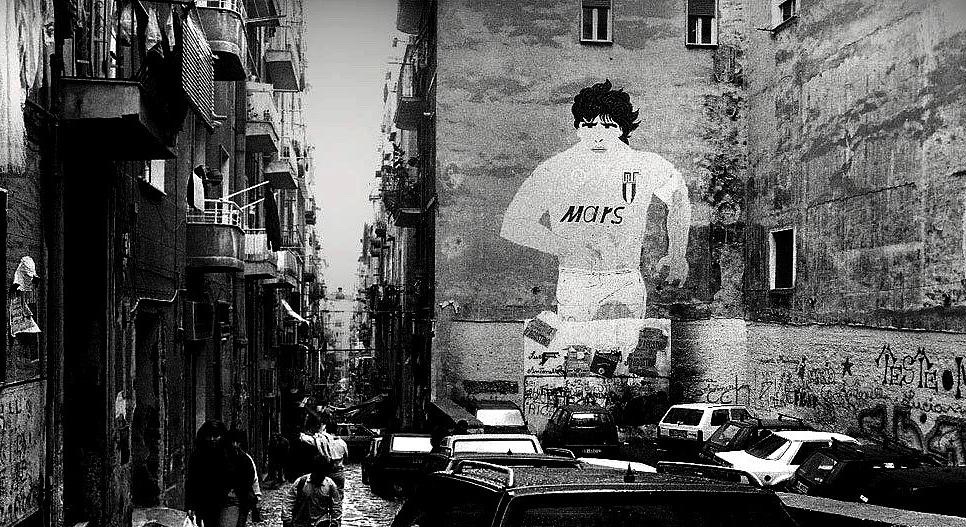

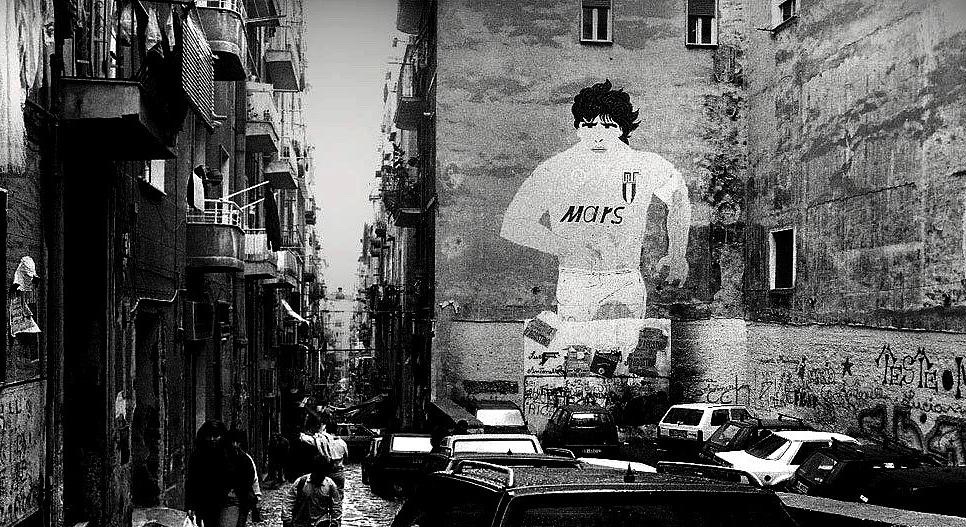

It would be wrong to say that the arrival of the Brazilian striker kicked off a golden age for Napoli. They had already secured the Scudetto the previous season for the first time in the club’s history and had added the Coppa Italia for good measure. They also had the mercurial

Diego Maradona in their squad, along with Bruno Giordano, who had joined in 1985, one year after the Argentine maestro.

When Careca arrived to complete the triumvirate of stars, though – which quickly became known as ‘Ma-Gi-Ca’ – the club was catapulted to a new level. Such a powerful cocktail was a heady brew, but as with any over-indulgence, there’s always the hangover to come. In 1987, that was way down the line. Napoli were on a roll and ready to set Serie A alight with their irrepressible football.

Any time he had arrived at a new club, Careca had quickly assimilated into the way the team played. His time with Napoli was no different. Some may argue that it would be easy to play alongside a talent such as Maradona in his prime, others would argue the reverse; but the rapidity with which the Brazilian striker struck up a relationship with the Argentine genius argued very much for the former – at least in his case anyway. They were the two elements of a dovetail joint that fitted perfectly together to build success for Napoli. Maradona was the light drawing defenders to him like moths to a flame, while Careca was the stiletto, the striker finding the space for Maradona’s carefully crafted passes and driving home the killer strike.

In his first season in Italy, Careca scored 18 goals across all competitions. If that seems a relatively small amount, remember this was his first time in Serie A where the price of goals was exorbitant and defences ruled. It was, in fact, an outstanding contribution to a season when, having pipped Juve to the title the previous season by three points, they finished second by the same margin to

Arrigo Sacchi’s AC Milan. Maradona top-scored in the league with 15 goals, but Careca was a mere two strikes behind him. A first-round exit in the European Cup – albeit to the might of Real Madrid – was probably the only dark moment of their season.

The following year, Napoli again finished as runners-up to a club from the San Siro, but this time it was Inter that lifted the title. Careca upped his goal tally to 19 in his second season, leaving him just three short of Aldo Serena who topped the charts to be awarded the

Capocannoniere title. It was in Europe, though, that their light blue star shone brightest.

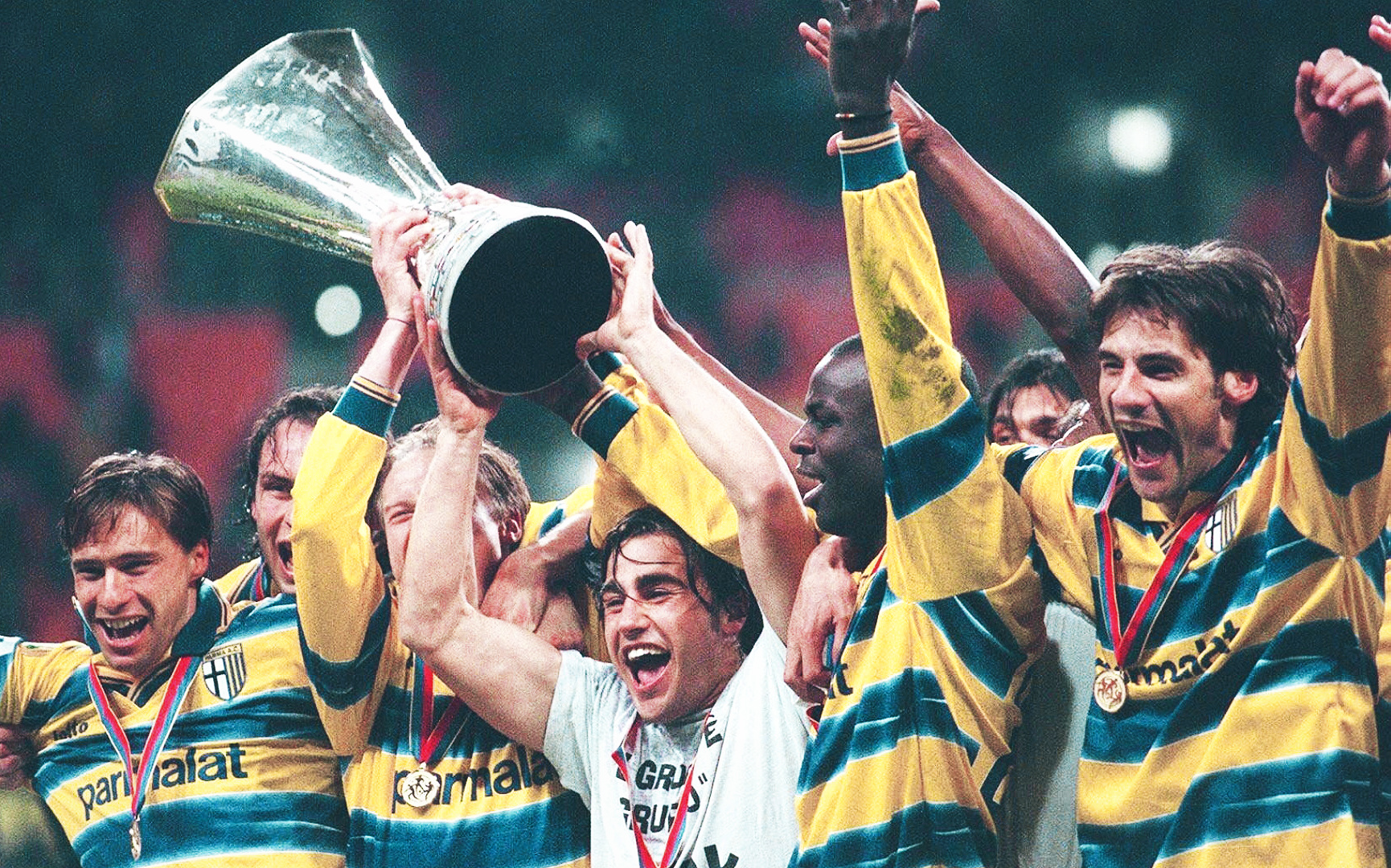

A lack of European success had been a yawning gap in the history of the

Partenopei. Whilst Juve and the Milan clubs had all claimed the biggest pot in European club football and Sampdoria, Parma and Lazio had garnered success in the Cup Winners’ Cup and UEFA Cup, Napoli had yet to win a major continental trophy.

Read |

Read | Naples: dancing to the beat of Diego Maradona since 1984

By now,

Ma-Gi-Ca had been broken up as Giordano had moved on to Ascoli, but it hardly seemed to check Napoli’s progress. Their second-placed finish the season before had given them a place in the UEFA Cup and a chance to claim a European prize for themselves. In the first round, they began in fairly inauspicious fashion, a 1-0 home victory against PAOK thanks to a Maradona penalty handing them a slender lead to take to Greece.

When Careca netted in the ninth minute in Thessaloniki, a comfort blanket was created that offered a smooth passage into the next round. A single second-half strike from Skartados did little to ruffle it.

The second-round tie against Lokomotive Leipzig looked a little more difficult, especially when Matthias Zimmerling scored to put the East Germans ahead. An equaliser by Giovanni Francini five minutes later put Napoli back in the ascendency with an away goal, and back at the Stadio San Paolo, another strike from Francini with just two minutes gone and an own goal by Heiko Scholz saw them safely through.

In the round of 16, a 1-0 win against Bourdeaux in France and a goalless draw back in Italy meant passage to the last eight. If the earlier rounds had been stodgy fare, it was now time for the serious business to begin, and in particular for Careca to show his worth once again.

The quarter-final was an all-Italian affair with Napoli pitted against the Old Lady of Turin. At the Stadio delle Alpi, a 2-0 win for the

Bianconeri looked to have put them well on their way to the last four, but back in Naples, a sterling home performance saw the home team level things up before going through in extra-time. The next task was a semi-final against Bayern Munich. It would be a tie dominated by Careca.

The first leg was played at the San Paolo, and Napoli executed the perfect home performance. For most of the first period it was a cagey affair, with both teams aware that the first goal would have a significant influence on the outcome of the tie. Caution was to the fore, and it took a bit of magic between the home team’s two stars to break the deadlock.

With just Maradona and Careca on an attacking sortie, the Argentine seemed boxed in by a trio of red-shirted defenders. Careca, however, had faith in his teammate and peeled away on a forward run. Ever aware of the possibilities open to him, Maradona neatly lifted the ball into the path of the onrushing Brazilian. As was almost invariably the case, the pass was inch perfect, and as a defender lunged to try and intercept, Careca brushed past him, controlled and then pulled the shot back across the goal and into the net. The crowd erupted as he ran towards them, kissing his shirt before being mobbed by team-mates – plus a few fans who had found their way onto the pitch. Napoli went into the break ahead.

The second goal came on the hour mark. A short corner led to Maradona hoisting a cross into the box to be met with a powerful header from Andrea Carnevale. A two-goal lead and a clean sheet that was preserved to the end of game brought a highly-satisfying conclusion to the game. It would now need a remarkable comeback from the Bavarian club if they were to turn the tie around two weeks later in the return leg.

Despite the need to score and fairly continuous pressing in the first period of the game, at half-time in the game at Munich’s Olympiastadion, the two-goal lead for the Italians remained intact. Bayern may well have been fretting that, as time ticked away, they would be compelled to force themselves forward in pursuit of a goal that may expose them to a Napoli counter laced with the guile of Maradona and the power of Careca. And so it was.

Original Series |

Original Series | The Football Italia Years

Careca struck just past the hour to put the visitors ahead. Maradona bullied a defender off the ball, then looking up saw Careca where he would inevitably be, free in the box and awaiting his pass. The Argentine supplied the assist; the Brazilian coolly netted. The lead was up to three, with the added bonus of an away goal, leaving Bayern now needing four. The lead in the game lasted a mere 120 seconds before Roland Wohlfarth netted after a defensive scramble, but it hardly seemed to put a dent in Napoli’s confidence as conceding three more looked a very slim possibility.

There was little to lose now, though, so Bayern continued to drive forwards, but the next goal was almost a textbook example of how to score from a breakaway. Losing possession on the edge of the Napoli box, Bayern were quickly exposed. A forward pass found Maradona driving forwards, but with a defender closing him down. In such situations, a look for a teammate is usually required. Maradona did so, knowing that Careca would be storming upfield in support, outstripping any covering defender. A sweet caress with his left boot saw the Argentine set his teammate in the clear.

Driving powerfully forwards, Careca fired ruthlessly into the net. It was a glorious goal, executed with sublime precision and involving just three passes after Bayern had squandered possession so expensively. Careca and Maradona hugged and the Italian fans celebrated noisily. With less than 15 minutes to play, it was surely the winning goal; Bayern now needed four again, but it simply wasn’t going to happen. A late goal by Stefan Reuter gave the Bundesliga leaders the slimmest of consolations, but as the whistle went, it was clear that the Maradona-Careca axis had simply been too proficient for them.

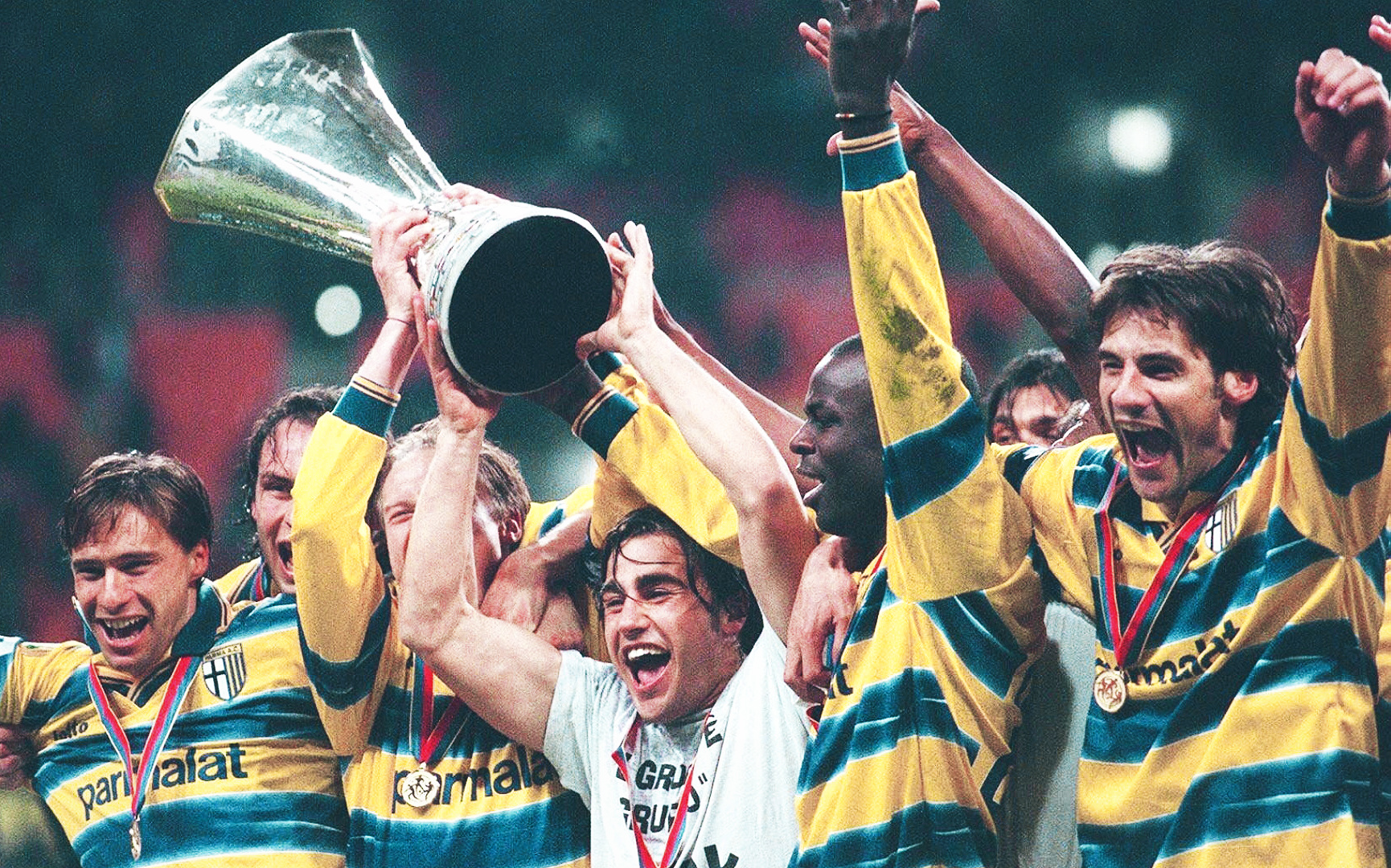

Another German team, VfB Stuttgart, awaited Napoli in the two-legged final. The first leg took place on 3 May in Naples, but it didn’t all as planned for the

Partenopei. Initially it looked like the Germans would avoid the rocks of Capri when the first 15 minutes passed fairly uneventfully, if with no little tension. A couple minutes later, a free-kick just outside the Napoli area was tapped sideways for

Maurizio Gaudino to shoot from distance.

While well struck, the ball seemed destined for goalkeeper Giuliano Giuliani. Whether there was a late slight swing in the flight of the ball is unclear, but the home stopper fumbled the save and only managed to divert it into his own net.

The home fans were stunned into a temporary silence as the Stuttgart players celebrated not only taking the lead, but perhaps more importantly, in the long run, having pocketed an invaluable away goal. On the home bench, heads were bowed as the Germans trotted back to their own half for the game to recommence. The remaining minutes of the first half were taken up with Napoli pressing forward but without any tangible reward. With just over 20 minutes to play, though, things swung back in the home team’s favour in a hugely controversial moment.

A cross into the German area was nodded on by Carnevale towards Maradona closing in at the far post. Attempting to control, the Argentine first touched the ball with his shoulder and then seemed to throw out an arm to bring the ball back towards him, before firing off a shot. The ball struck a German defender on the arm from no more than a yard away. Blue-shirted arms went up in appeal, but it was surely more in hope than expectation.

Greek referee Gerasimos Germanakos, with the impassioned howls of 81,000 in the crowd screaming for justice, pointed to the spot. The visiting players protested to no avail. German goalkeeper Eike Immel was booked for his trouble and Maradona coolly slotted home. To take something meaningful from the game, another goal would be needed, so the scorer raced into the net to retrieve the ball and back to the centre circle to get the game restarted. Maradona had done his bit, and now it was time for Careca to do his. He wouldn’t let Napoli down.

Read |

Read | Gianfranco Zola and Diego Maradona at Napoli: the student and the mentor

It was the 87th minute when another ball into the box found Carnevale. He controlled and laid it off to Maradona. Neatly lifting the ball past a defender, he almost reached the goal line before squaring the ball across to where his teammates should have been waiting. Inevitably, it was Careca in place. He controlled, touched the ball once, twice and then a third time as he manoeuvred past both a teammate and an opponent, before placing the ball wide of Immel and into the net for the most precious of winning goals. It was a typical Careca strike: professional, polished and highly valuable. He would repeat the act two weeks later when Napoli travelled to the Neckarstadion for the return leg.

If the first game was tight and tense in the fiery atmosphere of the San Paolo, the game in Germany was full of drama and goals. The Germans started brightly, knowing that, thanks to Gaudino’s goal in Naples, a 1-0 victory would see them to victory on away goals. An early cross into the box found the head of skipper Karl Allgöwer, but his attempt was comfortably smothered by Giuliani. When the first goal came, though, it was for the visitors.

Brazilian midfielder Alemão had joined the club the previous year, and with just over 15 minutes played, it looked like an injury would curtail his presence on the pitch. After treatment, he played on and, a couple of minutes later, gave Napoli the lead. Racing onto a through ball, he held off closing defenders to prod the ball past Immel. The goalkeeper touched the ball but couldn’t prevent it rolling into the net to give Napoli their away goal.

The lead was short-lived, however.

Jürgen Klinsmann had missed the first leg but was now back to lead the Stuttgart line and, on 27 minutes, levelled the scores on the night. A corner from the Stuttgart left found the striker’s blond locks at the far post as he towered above Ciro Ferrara, who hardly seemed to jump, and a fierce header back across goal brooked no argument from the goalkeeper. Ferrara would have his own say shortly afterwards.

The clock was ticking towards the last five minutes of the half when Maradona struck a corner in from the Napoli left. Klinsmann headed clear but it fell straight to Maradona, who nodded back into the German area. The ball looped towards the six-yard box, but Immel appeared transfixed on his line when he could surely have taken a couple of steps forward and gathered it. Ferrara, up from his defensive post for the corner, wasted no time and swept home the ball. It was now 1-2, and with two away goals to add to their lead in Italy, Napoli appeared to be on the way to their first European trophy.

The Germans were now compelled to push forwards, but in such circumstances, the rapier striking of Careca is always an inherent danger. Just past the hour mark, a break saw Maradona running forward, but halted by a defender and looking inside, the man he expected to be up in support was there, outstripping the defender who was trying in vain to keep pace with him.

Maradona slipped the ball inside, and as Immel came out, Careca neatly clipped the ball over him to make it 5-2 on aggregate. The deal was done. An own goal by Fernando De Napoli five minutes later offered false hope, and a late goal by Olaf Schmäler on 90 minutes mere consolation, but Napoli were home and dry. They lifted the UEFA Cup, with Careca the top scorer in the competition.

Read |

Read | The decline of Napoli post-Maradona: from Paradiso to Inferno

The following season was something of a consolidation for Careca, as he only netted 10 goals across the season. They were all valuable strikes as Napoli again lifted the Scudetto, two points clear of Milan. It was party time for Napoli with their fans, and Careca was very much at the centre of things, as the Brazilian’s relationship with Maradona drove the team forward. Maradona scored 17 goals but was booed everywhere he went after Argentina had eliminated the

Azzurri from the World Cup on penalties in the semi-final – ironically at the San Paolo. Careca’s World Cup campaign was much more subdued. Although he scored twice in four games, it was a below-par result for the

Seleção to be eliminated in the last 16.

If the 1989/90 season had been a triumph for Napoli, capped off with what would be Careca’s last trophy with the club when they defeated Juventus 5-1 in the Supercoppa, the following years would see a steady decline as the

Partenopei floundered on their own set of rocks. Rumours had been rife that Maradona’s off-field life had deteriorated amid reports of inappropriate liaisons with members of the Camorra and involvement with prostitutes and drugs.

The latter was confirmed on 17 March 1991 when the Argentine failed a drugs test following a game against Bari. He had tested positive for cocaine. Despite the traumas and upheavals of the season, Napoli finished in eighth-place in the league. It hadn’t been a stellar defence of their title, but given the goings on around the club, and particularly with its star player, it was an achievement of sorts.

The golden period had now lost a lot of its glitter, but Napoli still had Careca, plus a bunch of other players, such as

Gianfranco Zola – an apprentice of Maradona, at least with regard to matters on the field – breaking through into the team. Spearheading the club’s efforts, Careca bagged a highly-credible 15 goals to take Napoli to fourth place in Serie A. It was a performance way above expectations as the club spiralled downwards.

The burden was too great, however, and that season would be Careca’s last hurrah as a top-line striker. The following term, his last with the club, he would score just seven goals as mid-table mediocrity dragged Napoli, the once strutting all-star team, back into its cloying fold.

The Brazilian, now nearly 33, would be shipped out of Italy to play for Kashiwa Reysol in Japan’s formative J League, scoring 40 goals in four years there before returning to Brazil for a last wander around three clubs. In his time in Naples he had scored just five short of a century of goals in 225 games, making him the sixth-highest scorer in the club’s history.

Goals are very much the defining measure of a striker, but coupled with that is the value of each one. The fourth goal in a 5-0 victory is good, but its value pales when compared to the winner in the last few minutes of a European final. Careca scored so many goals that really counted for his team, and the fans at the San Paolo loved him even more for that.

In the brief years he was in tandem with Maradona, Napoli became a team capable of taking on anyone and winning out, with each partner of equal worth. If there’s a fitting epitaph to the time Careca spent with the

Partenopei, perhaps it’s that when paired with one of the greatest players of all time, he delivered and lost little in comparison.

By Gary Thacker @All_Blue_Daze

Antônio De Oliveira Filho was born in the city of Araquara in the Brazilian state of São Paulo on 5 October 1960. His nickname, Careca - which roughly

thesefootballtimes.co

thesefootballtimes.co

thesefootballtimes.co

thesefootballtimes.co

thesefootballtimes.co

thesefootballtimes.co

thesefootballtimes.co